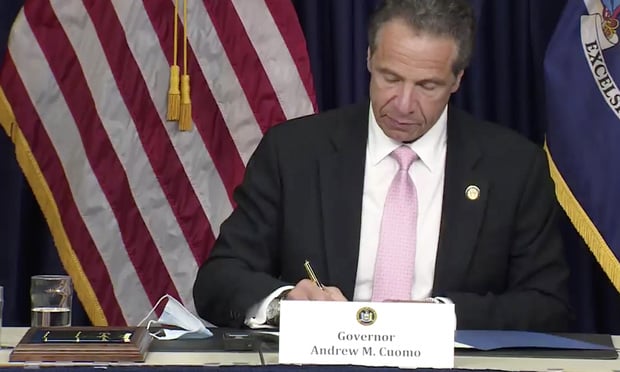

AP Photo Courtesy of the Office of New York Governor Andrew M. Cuomo.

AP Photo Courtesy of the Office of New York Governor Andrew M. Cuomo.On Oct. 6, 2020, New York Law Journal published an article by Judge Thomas F. Whelan, “Executive Orders: A Suspension, Not a Toll of the SOL,” arguing that Governor Andrew M. Cuomo lacked authority under Section 29-a of Executive Law to issue Executive Order 202.8 tolling the statute of limitations or other time limits during the COVID-19 pandemic, and therefore the word “toll” in the governor’s executive order 202.8 should be construed as an extension of time.

If the article is correct, any deadline in a civil matter that falls between March 20, 2020 and Nov. 2, 2020, must be complied with by Nov. 3, 2020. The article disagreed with the previously published articles in New York Law Journal, to wit, Thomas A. Moore and Matthew Gaier, Medical Malpractice, “Toll on Statute of Limitations During COVID-19 Emergency,” NYLJ, June 1, 2020; Patrick M. Connors, New York Practice, “The COVID-19 Toll: Time Period and the Courts During Pandemic,” NYLJ, July 17, 2020.

Section 29-a was enacted in 1978 as a part of Article 2-B of Executive Law titled State and Local Natural and Man-Made Disaster Preparedness. In the past 42 years, Section 29-a was amended twice, once in 2012 when the requirement for seeking the advice of the commissioner on disaster preparedness was removed (Laws 2012, ch 55, section 8), and again and more significantly on March 3, 2020, in anticipation and preparation for the COVID-19 pandemic (Laws 2020, ch 23).

The March 3, 2020 amendments to Section 29-a (1) are noted below (matter in brackets is old and is omitted, and in bold is the new language):

Suspension of other laws. 1. Subject to the state constitution, the federal constitution and federal statutes and regulations, the governor may by executive order temporarily suspend [specific provisions of] any statute, local law, ordinance, or orders, rules or regulations, or parts thereof, of any agency during a state disaster emergency, if compliance with such provisions would prevent, hinder, or delay action necessary to cope with the disaster or if necessary to assist or aid in coping with such disaster. The governor, by executive order, may issue any directive during a state disaster emergency declared in the following instances: fire, flood, earthquake, hurricane, tornado, high water, landslide, mudslide, wind, storm, wave action, volcanic activity, epidemic, disease outbreak, air contamination, terrorism, cyber event, blight, drought, infestation, explosion, radiological accident, nuclear, chemical, biological, or bacteriological release, water contamination, bridge failure or bridge collapse. Any such directive must be necessary to cope with the disaster and may provide for procedures reasonably to enforce such directive.

The memorandum in support of the bill by the sponsors (Senator Ortiz and Assembly Member Stewart-Cousins) explains that the legislation was enacted to broaden the governor’s authority to deal with the novel COVID-19 pandemic.

This legislation is necessary to allow New York to manage, prepare, respond to, and contain such threat, and to respond with appropriate action to protect public health and welfare. New York received its first positive case on March 1, and more are expected. These changes ensure the governor has necessary legal authority to confront these emergencies.

Section 29-a applies to “any statute, local law, ordinance, or orders, rules or regulations, or parts thereof.” The word “toll” is not in common usage when applied to most laws. It has a special meaning, however, in the context of statute of limitations. Toll means interruption of the calculation of time of the statute of limitation and resumption of the calculation after the toll’s expiration. For multiple helpful examples of how a toll operates, please see David L. Ferstendig, et al., “The Scope of the COVID-19 Toll of CPLR Time Limits,” NY St Law Digest 717, August 2020. In contrast, extension of a statute of limitation merely means that the deadline for filing an action is extended for the time stated.

Section 29-a authorizes the governor to issue an executive order or a directive for the suspension of “any statute, local law, ordinance, or orders, rules or regulations, or parts thereof.” “Suspension” is defined in Black’s Law Dictionary to include “[t]he act of temporarily delaying, interrupting, or terminating something [suspension of business operations] [suspension of a statute]” (Black’s Law Dicti0nary [11th ed 2019], suspension [Note: online version]). Suspension of a statute of limitation means both an interruption or termination (i.e., toll) or temporarily delaying (i.e., extension). Executive Law 29-a gave the authority to the governor to issue an extension of time and/or a toll as necessary to cope with imminent, urgent or impending disaster.

That the word “suspension” or “suspend” in a context of statute of limitations could mean a “toll” is amply supported by case law. In Roldan v. Allstate Ins. Co., the Appellate Division held that the statute of limitation was suspended from the time when the Supreme Court erroneously granted defendant’s motion to vacate the judgment in the underlying action through the time when the Appellate Division reversed the order vacating the judgment, and “[b]ecause of this toll, we conclude that the plaintiff’s causes of action for indemnification and bad faith negotiations are not time-barred” (149 AD2d 20, 31-35 [2d Dept. 1989]).

When facing whether a particular situation warrants tolling of a statute of limitation, the Court of Appeals has used the word “suspend” to explain a toll (see e.g. Ratka v. St. Francis Hosp., 44 NY2d 604 [1978] [“The court reasoned that the two-year Statute of Limitations for such action had not tolled on account of infancy of the surviving child”; “The infancy of decedent’s children will not suspend the running of the two-year Statute of Limitations for commencement of a wrongful death action”]; Baez v. New York City Health & Hosps. Corp., 80 NY2d 571 [1992] [“CPLR 208 does not apply to toll the Statute of Limitations”; the executor’s failure to timely commence an action on behalf of the infant children “does not suspend the running of the applicable statute of limitations period”]).

The United States Supreme Court also described a “toll” as suspension of a statute of limitation. In Artis v. District of Columbia (__ US __, 138 S Ct 594 [2018]), Justice Ruth Bader Ginzburg, writing for the majority, stated:

“First, the period (or statute) of limitations may be ‘tolled’ while the claim is pending elsewhere. Ordinarily, ‘tolled,’ in the context of a time prescription like § 1367(d), means that the limitations period is suspended (stops running) while the claim is sub judice elsewhere, then starts running again when the tolling period ends, picking up where it left off. See Black’s Law Dictionary 1488 (6th ed. 1990) (“toll,” when paired with the grammatical object “statute of limitations,” means “to suspend or stop temporarily”). This dictionary definition captures the rule generally applied in federal courts. See, e.g., Chardon v. Fumero Soto, 462 US 650, 652 (1983) (Court’s opinion “use[d] the word ‘tolling’ to mean that, during the relevant period, the statute of limitations ceases to run”). Our decisions employ the terms ‘toll’ and ‘suspend’ interchangeably. For example, in American Pipe & Constr. Co. v. Utah, 414 US 538(1974), we characterized as a ‘tolling’ prescription a rule ‘suspend[ing] the applicable statute of limitations,’ id. at 554; accordingly, we applied the rule to stop the limitations clock, id. at 560-561.” (Artis, 138 S Ct at 601-602.)

There is no legal distinction between “suspension” and “tolling” of a statute of limitation. “Suspension” could include tolling of a statute of limitation given the intent of an executive order.

Turning to Executive Order No. 202.8, issued on March 20, 2020, the first step to understand its intent is to review the language used, which in relevant part provides:

In accordance with the directive of the Chief Judge of the State to limit court operations to essential matters during the pendency of the COVID-19 health crisis, any specific time limit for the commencement, filing, or service of any legal action, notice, motion, or other process or proceeding, as prescribed by the procedural laws of the state, including but not limited to the criminal procedure law, the family court act, the civil practice law and rules, the court of claims act, the surrogate’s court procedure act, and the uniform court acts, or by any other statute, local law, ordinance, order, rule, or regulation, or part thereof, is hereby tolled from the date of this executive order until April 19, 2020. (Emphasis added.)

Several extensions of Executive Order No. 202.8 have been issued, and on Oct. 4, 2020, the governor issued Executive Order No. 202.67, which in relevant part provides:

The suspension in Executive Order 202.8, as modified and extended in subsequent Executive Orders, that tolled any specific time limit for the commencement, filing, or service of any legal action, notice, motion, or other process or proceedings as prescribed by the procedural laws of the state, including but not limited to the criminal procedure law, the family court act, the civil practice law and rules, the court of claims act, the surrogate’s court procedure act, and the uniform court acts, or by any statute, local law, ordinance, order, rule, or regulation, or part thereof, is hereby continued, as modified by prior executive orders, provided however, for any civil case, such suspension is only effective until November 3, 2020, and after such time limit will no longer be tolled. (Emphasis added.)

The word “tolled” clearly and unequivocally appears in the Executive Orders.

Governor Cuomo had issued an Executive Order after Superstorm Sandy (Executive Order [Cuomo] No. 52, Oct. 31, 2012), which included extensions of time, suspending:

Section 201 of the Civil Practice Law and Rules, so far as it bars action whose limitation period concludes during the period commencing from the date that the disaster emergency was declared pursuant to Executive Order Number 47, issued on October 26, 2012, until further notice, and so far as it limits a courts authority to extend such time, whether or not the time to commence such an action is specified in Article 2 of the Civil Practice Law and Rules.

Similar language appears in Governor George E. Pataki’s Executive Order No. 113.7, issued on Sept. 12, 2001, after the 9/11 attack (see also Deltoro v. Arya, 305 AD2d 628 [2d Dept 2003] [treating Executive Order No. 113.7 as an extension of statute of limitation]).

Clear language of the executive order issued to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic, as compared with the prior executive orders, indicates that the inclusion of the word “tolled” was intended to avoid any confusion.

This interpretation is in line with “the goals of the disaster action necessary” (Executive Law 29-a [2] [e]). The COVID-19 pandemic was not a single event emergency. The pandemic has caused unprecedented shutdown and disruption of social life including the administration of justice. It has and continues to cause immense interruptions in legal practices and the pandemic’s end is nowhere near in sight. The goal of the executive order was to assist and aid people in coping with the severe health crisis during the COVID-19 pandemic (Executive Order No. 202.8).

The application of a toll in this context was a necessary and eminently reasonable one. The governor had the authority under the statute to issue Executive Order No. 202.8 and its extensions. Construing Executive Law §29-a to limit the governor’s authority to an extension of time but not tolling of statute of limitations is inconsistent with the plain meaning and the purpose of the statute.

Stampede to comply with all deadlines by Nov. 3, 2020, when neither most courts nor most practices are operating on full capacity, is unreasonable and would be harmful to many practitioners and their clients who have been struggling to cope with the new realities and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The bar and the bench have been working together to forge paths for smooth transition into the new reality. Pitfalls in that effort should be avoided.

Souren A. Israelyan is the principal of Law Office of Souren A. Israelyan, in New York City, a solo practitioner with trial practice focusing on personal injury matters.